The recent commemoration of Anzac Day's 100th anniversary was as good a reminder as anything of the importance of keeping records of our history. Photographs from that time may be grainy, blurry and often creased, but they still manage to provide incredible insight into a very different time. This, of course, is even more important now as there are no remaining survivors of that campaign – pictures and words are all we have left.

Which begs the question. In another 100 years, what memories will today's generations have left to share with our counterparts of the future?

On the surface this seems a ridiculous question. After all, we take billions more photos and write trillions more words today than were collected in the early 20th century. But it's not that simple. There are two major problems, both relating to the fact that so much of what could be 'tomorrow's memorabilia of today' is not stored in permanently useful formats.

The risk of inaccessibility

Vint Cerf is a Google vice president these days but the 71-year-old is widely acknowledged as one of the three 'fathers of the internet'. Cerf recently warned that we may be heading towards a digital 'dark age' in which today's words and images are lost forever as computer operating systems, file formats and digital storage inevitably become obsolete over time.

That may sound far fetched, but if you think about the fact that more and more modern computers don't include a DVD drive, let alone a floppy disk drive, it's actually an issue that is relevant right now. If you have archives stored on DVDs, those records may be inaccessible in the very near future – even if they haven't deteriorated or become corrupted in the meantime.

Cloud storage may seem to be a future-proof solution to this issue, but we need to remember that the ground-based computers that store our information in the 'cloud' are owned by private companies. Very likely those companies won't be around in 100 years. Even if they are, those services rely on someone having access to the files, which raises the issue of digital wills.

And before any of this becomes a consideration, there's the problem that a lot of data is never properly stored at all. For instance, a UK survey indicated that a third of Britons lose photographs that they've taken on a smartphone but have never backed up in any way.

The risk of incomprehensibility

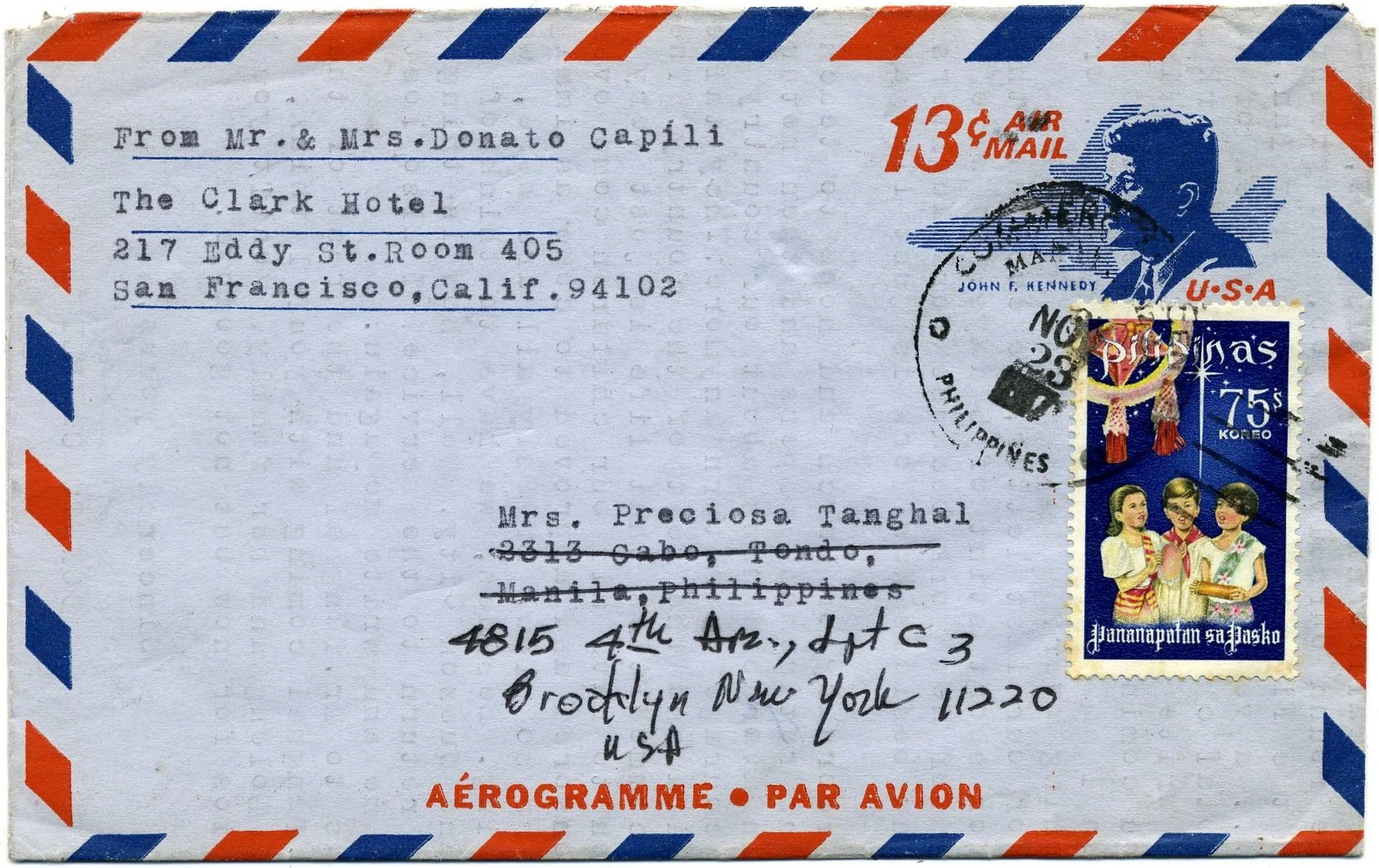

When my wife and I spent two years travelling 'before kids', we regularly sent letters (remember aerograms?) home as well as keeping paper diaries. We still have all of that correspondence as keepsakes.

When my daughter recently spent a few months travelling, she didn't send a single letter home. We heard from her often, via text messages and Skype calls, but in terms of accumulating a lasting and coherent record of her journey we have very little. She did take lots of (digital) pictures, none of which have been printed yet, and she started a journal but ran out of time to complete it. My bet is she'll never find that time.

The same thing happens in workplaces. There is copious communication, but who wants the job of sifting through terabytes of email chains to try and find the 'gems' that are worth keeping for posterity? The reality is that most businesses risk leaving lots of data but little of meaning to those who might run them in the future.

Guaranteeing history

The only way of guaranteeing that future generations will benefit from what we have learnt is to document and print the best of what we know. We need to print photographs and store them in albums (or just print albums in the first place). And we need to write the stories of our successes and failures, and print those too either as books or in folders.

The alternative is to risk being lost in the digital dust.

As usual, if you have any questions or comments, please add a comment below or contact me.